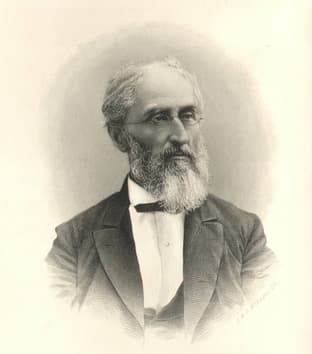

1812 — 1884

美国基督教公理会

Printer, editor, writer, scholar, and diplomat. “Founder of American Sinology” (Guan 114)

Samuel Wells Williams was born in Utica, New York, on September 22, 1812, into a family distinguished for piety, learning, and long lives. His father, Deacon Thomas Williams, established a successful and highly regarded printing business. He also rose to the rank of colonel in the War of 1812.

His mother was marked by “sobriety … untiring diligence and thrift” (Guan 8). Her example “furnished a model for every mother” (9). She bore ten children who survived, nine of whom were sons. Despite poor health, she kept them constantly busy, as she did their household servants. She was attentive also to the needs of the young men in her husband’s printing business. After she joined the Maternal Association in 1825 and experienced a personal spiritual revival, “she became exceedingly burdened by the spiritual necessities of her children” (9), for whom she prayed often and fervently.

In addition to teaching in the Sabbath School and caring for sick people in the community, her chief “interest was aroused in the cause of missions; from this her attention never swayed” (10). At one point, she put into the church offering basket a note saying, “I give two of my sons” (11).

Samuel Wells Williams was the oldest of fourteen children. Because of his mother’s ill health, he was for some years put into the care of his mother’s aunt, Miss Dana. He “treasured to the end of his life kindly memories alike of her nurture and admonition” (11; see Ephesians 6:4 KJV). As a child, he was “wonderfully healthy” (Kaiser 6) and continued to be until he suffered injuries as an old man.

His schooling began when he was six or seven, under the instruction of one tutor after another and in a small school, where he learned the rudiments of English, and then the standard classical texts. A classmate later wrote that “Wells was always studious, and in his spare hours was almost constantly reading some book – usually one brought from his father’s shop at home – in which he was ever deeply absorbed,” including an account of missionary work in the Sandwich Island, which “he read with lively interest… . When out of school and at play he had plenty of fun and frolic… . He was a general favorite, not only with his teacher but with all his acquaintances and was so universally well-informed that [the teacher] often referred to him to answer some question that the others could not.” He also had a reputation for “perfect truthfulness” (26).

In addition to “common school,” which the town organized, Sunday school played a huge role in the intellectual and spiritual formation of young people, including Williams. Students were expected to memorize the entire Bible. Williams received a certificate for reciting the New Testament from memory without mistake. Not only did he commit the words of the Bible to memory, but he also learned the ponder them and then, as a teacher in the Sunday school, to impart the truths of Scripture to others. This early absorption of Scripture, coupled with a strong moral and ethical emphasis by the teacher, shaped not only his mind but also his theology and fundamental orientation toward life and ministry. (Kaiser 12-13).

At the age of eight, he was inspired by the departure of a printing missionary to Ceylon, which sparked his interest in missionary work.

He began attending Utica High School in 1829. Here he first learned about, and became utterly fascinated with, the natural sciences, so much so that he determined to become a naturalist.

This strong sense of vocation received a sudden challenge when his father informed Wells that Rufus Anderson, the chairman of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) had asked his father to refer to him some promising young man to serve as a printer for the mission in China.

In 1831, he and his brother Frederick both made a profession of faith and joined the First Church of Utica, the occasion of which his son and biographer wrote that this “act was attended … by the blessing of God, with a genuine regeneration of his nature, which beginning with the more severe control of a naturally impatient temper, became conspicuous to his acquaintances” after the death of his mother. “From this time forward something of the sweetness of [his mother] seems to have entered into his character … the habit and disposition of shaping his daily duty and conversation with reference to a personal and ever-present God began and never diminished” (30).

In July of 1832, a week after receiving his father’s letter about service in China, he wrote, “I believe that I have, by the light which God has given us in the Bible, examined the question, and as far as I am acquainted with my own heart, I am willing to go. Many doubts and difficulties arise… . But I also look at the other side and see three fourths of the world in a state of heathenism, or half-idolatry – then that side of the scale weighs heaviest. The way of duty is the plainest and in the end is easiest. ‘Go ye into all the world’ (Mark 16:15) still remains as a last command, and one which should be considered attentively. I should think little of that Christian’s ardor or sincerity who cannot do anything for his Savior” (44).

Acting on this conviction, after much prayer he agreed to complete a crash course on the arts of a printer in only six months. His deep love for his father since his mother’s death made parting from home and family exceedingly difficult, but, as he wrote, “turn the page and consider the object, to evangelize the world,” and one who as “put his hand to the plough has but one way to look,” that is, forward.

Perhaps we should note that Williams was very young (21) when he embarked on his career as a missionary. He had no theological education or experience in church ministry. Unlike Robert Morrison, he had no formal missionary training.

He sailed with the Rev. Ira Tracy on the Morrison, owned by that fervent Christian and friend of missions, Mr. Olyphant, on June 15, 1833. Williams and Olyphant formed a very close friendship in the coming years. The ship arrived at Whampoa, twelve miles below Canton, on October 25, 1833. They were then rowed up to the row of buildings called “factories,” named for the “factors,” the limited number of foreigners who had been authorized to do business in Canton. This community of about three hundred men from “all nationalities” inhabited long buildings that stretched about five hundred feet back from the river.

The foreigners had strict limitations imposed upon them. They could only walk along the narrow strip of land in front of their property. If they went into the city, they would most likely be robbed. On the other hand, they enjoyed close and cordial relations among themselves.

Williams immediately entered the warm fellowship of Robert Morrison, the first Protestant missionary to China, and Elijah Bridgman, the first American missionary there. He and Bridgman struck up a friendship that lasted several decades. He also met Morrison’s son John, Edwin Stevens, and the first convert, Liang Afa.

The Manchu government imposed severe restrictions upon all their activities, especially forbidding foreigners to learn Chinese. Chinese caught teaching them would suffer harsh penalties, including death. In spite of this, he was able to get a “teacher of considerable literary attainments,” who kept a foreign lady’s shoe always on his desk so that, if the police came, he could claim that he was a Chinese manufacturer of foreign shoes (58).

Bridgman had begun publishing the Chinese Repository in May of 1832. This journal sought to inform merchants on the conditions of China and thus win their sympathies and perhaps contributions to the work of missionaries. He brought Williams into that work as manager of the press at once. Williams’s first articles on “Chinese Weights and Measures” and “Imports and Exports of Canton” appeared in February 1834, demonstrating his ready intelligence and early grasp of the situation and the printer’s craft. He later began to write on Chinese natural history, until greater facility in language enabled him to compose learned articles on Chinese literature. He would go on to become, with Bridgman, one of the “distinguished successors” to the “early pioneer missionary linguists and translators” (Field, in Fairbank 42).

Along with teaching Williams how to run the East India Company press, Bridgman served as his mentor, impressing upon him the importance not only of acquiring the language, but also of “the necessity of constant and accurate observation of the peculiar people among whom they lived; avoiding the temptation to consider merely the odd and picturesque elements of Chinese civilization; training his daily life to bear the minute and suspicious scrutiny of a hostile society” and other essentials of missionary success.

As Williams ventured out into the composition of longer articles, Bridgman also supplemented his meager training in English, so that eventually he could write “sentences of singular vigor and expressiveness. Though never free from a certain clumsiness of diction in his longer works, the terse and direct quality of his dictionary definitions has received the commendation of multitudes of students and contributed distinctly to the advancement of philology” (64).

Like most missionaries, Williams reacted emotionally to the pervasiveness of the idolatry that he saw all around him. “To see the abominations against the honour of Him who has commanded, ‘Thou shalt have not other gods before me,’ and not be affected with the deep sense of the depth to which this intellectual people has sunk, is impossible to a warm Christian man… . And is not such a mass of fellow immortals entitled to deep commiseration, to large and combined effort?” (64).

Notice the lack of condescension here, and the presence of pity for those walking in spiritual darkness.

In addition to articles for the Chinese Repository, his first task was to print the Chinese Chrestomathy begun by Elijah Bridgman. Meant to help younger missionaries, merchants, and diplomats, this major reference work (over 700 pages) combined the functions of a dictionary and reader about almost all aspects of Chinese life. Two of Williams’s coworkers in the press were Portuguese, so he had to learn that language as well as Chinese. Later, Williams added to the book so much material that his contributions amounted to more than half its content.

Since he could only safely engage in this sort of work, “he was able to devote his first year in China almost wholly to teacher and dictionary” (65). “Understood in the light of the entire history of Christianity in China, the remarkable control and patience with which Williams approached the mission task is rapidly revealed to be a wise and tempered strategy that attempted to cope well with the reality of Qing Dynasty China at the opening of the nineteenth century” (Kaiser 25).

Still, he would venture out sometimes and try to have conversations with local people. He also helped to conduct worship services on foreign ships whose captains were Christians. In general, he found the sailors very receptive to the gospel, but Chinese in general displayed only profound indifference.

The enormity of the tasks facing him – learning Chinese and converting China to Christ – almost overwhelmed him, until he realized that all he had to do was learn one word at a time and seek to communicate the gospel to the servants and coworkers around him, leaving the eventual results to God. Discouragement and gloominess led him to “put on as cheerful a face as I could assume, loving all mankind and trying to get those to love me who could” (67).

He found great motivation in the knowledge that the Chinese Repository was becoming an essential tool in the task of mobilizing and equipping Westerners to relate more knowledgably with Chinese and to proclaim the gospel to them with greater effect. The decades-long demand for this publication, which immediately received praise, confirmed his view of its strategic value.

The death of Robert Morrison in August 1834 affected him and his colleagues deeply. Though aware of Morrison’s faults, they rightly perceived him as a great Christian and a giant among missionaries and scholars alike. Soon, the loss of Morrison was partly compensated for by the arrival of Dr. Peter Parker, whose eye surgeries earned all of them much relief from the hostility of Chinese officials. The faithful friendship and strong support of the American merchant and ship owner Olyphant enabled them to keep going.

They still could not publish any books in China, however, so the mission decided to move the press to Macao, to which Williams moved in December 1835. He resumed work on Medhurst’s Chinese Dictionary of the Hokkien Dialect, as well as writing for the Chinese Repository. We can imagine that these tasks led to his becoming the great Sinologist of future fame. They also made a major contribution to bridging the gap between China and the West.

He suffered from the effects of the heat and humidity in southern China, feeling “lassitude, … languor and laziness combined; you wish to do but the flesh rebels,” his whole body covered with perspiration all day long (83). Even thinking took effort.

Williams liked his house, however, “a two-story affair with twelve rooms, each twenty feet square, and two lower rooms besides… . Two trees … constitute my garden, while beyond this and quite separate from my building is a cook-house. For household I have a porter, a comprador, a coolie, a cook, a printer and four little boys; in all, nine who live in the basement. The printing-office is under the parlor, and is a light room - when the sun shines. Besides all the rest there is a verandah on one side of the house, extending about sixty feet, which is a great convenience, indeed an absolute necessity in this weather” (83).

Despite his focus on language study and printing labors, he went with other missionaries from time to time into the surrounding countryside to distribute Christian literature. Like others in those days, he often found the people to be friendly and quite interested in books. He also encountered indifference, however, as we have noted, and occasionally some hostility. On the other hand, he wrote, “filth and misery appear everywhere to be concomitants of heathenism” (91).

Early in 1837, Edwin Stevenson died of illness, leaving Williams feeling bereft. The four missionaries had become “so wondrously knit together and enjoyed sweet communion. But Stevens was the joy of [the four],” who delighted in his humor, good sense, judgment, zeal in caring for his foreign flock, and zeal in visiting Chinese (92). During this time, they also developed “generous and large-hearted views of their common Christianity” and a great distaste for denominational barriers and prejudices (92-93).

Indeed, what later came to be called the Ecumenical Movement began on the foreign mission field, where people of various ecclesiastic affiliations learned to treasure unity in Christ above denominational loyalties.

In Macao, there were some Japanese staying with Charles Gutzlaff (1803-1852), who had been shipwrecked off the coast of America and brought to China in hopes of returning them to Japan. In July of 1837, Williams set off with a party that included Gutzlaff, a Mr. and Mrs. King, and Dr. Peter Parker to convey these men back to Japan, hoping also to demonstrate “civilization and Christianity to the Japanese whom they met as preparation for later missionary efforts” (94). The party returned to Macao in August, the mission having been unsuccessful. As a result of his contacts with Japanese both on this voyage and in his printing office, however, Williams “began a serious study of the language” from one of the men they had tried to return to Japan. He “prepared a translation of the Gospel of Matthew into Japanese for the instruction of the seven who had all been given employment by foreigners,” then “a small vocabulary Japanese words,” followed by “a translation of Genesis” into Japanese. “By these efforts he achieved the conversion of at least two of the sailors and gained a knowledge of the common people sufficient for conversational purposes” (100).

From these labors, we can see his zeal for the conversion of the lost, his energy, and his unusual skill in acquiring new languages.

Without going into detail, we may note that the First Opium War forced all foreigners to leave Canton for Macao, where he lived with the English missionary, Mr. Lay. While there, more opportunities for exercise restored his health, which had suffered greatly from the confined quarters of Canton. For the rest of his life, he spent an hour a day riding, rowing, or walking. His biographer attributes Williams’s “long life and freedom from illness” to this lifelong discipline of caring for his body (106).

At the same time, however, he suffered from extreme loneliness and longing for his family and friends back home. He compensated for this partly by walking among the Chinese in the neighborhood and getting to know them and their customs. Such close acquaintance led him to believe that “the mind of a heathen is dark enough, too dark to explain to you; a long work of patience and persevering labor is necessary” before they would be made receptive to the gospel (109). Thus, he said, “our sufficiency is of God. If the hearts of sinners at home, in Christian America, are so obdurate, will it be surprising if the consciences of the heathen are scarred with a hot iron?” (109).

As Britain and China edged toward armed conflict, Williams could see that Commissioner Lin was a superior man but hampered by his ignorance of foreign nations and their power.

Along with Bridgman, at first he expressed approval of the use of force by the British to gain the right to engage in commerce as an equal nation, even though the immediate aim of Britain (and other powers) was to continue the notorious opium trade.

At the same time, however, Williams made clear his opposition to the opium trade and initially expressed approval of Commissioner Lin’s desire to stop it. He hoped that “the English would recognize the righteousness of this act,” that is, Lin’s throwing opium into the sea, “however much it violated ‘the so-called law of nations’” (Fairbank 251). “By 1840,” however, “Williams was recommending for China ‘a hard knock to rouse her from her fancied goodness and security’” (Miller, in Fairbank 251). He explained that “in this struggle now going on we see the progress of freedom and Christianity over the opposition of ignorance and exclusion” (Fairbank 252). With Bridgman and Abeel, he printed a circular declaring, “In China we see a supremacy no less lofty and unjust in its pretension, not only taking inalienable rights from man, but Presumptuously encroaching on Jehovah’s prerogatives, attempting to abrogate His laws and stigmatizing the religion of Jesus Christ as based and wicked” (Fairbank 253).

For that and other reasons, they wrote further, it was erroneous to think that “the war was being waged ‘to perpetuate the opium trade,’” and “that there was a concealed object of conquest on the part of England” (Fairbank 253).

Later, however, in a letter to his father in 1841, he “condemned the war as totally ‘unjust’ … because of its ‘intimate connections’ with the opium trade” (Fairbank 253). He wrote further, “The whole [English] expedition is an unjust one in my mind on account of the intimate connection its sending here had with the opium grade… . For my part, I am far from being sure that this … is going to advance the cause of the Gospel half so much as we think it is” (122).

Nevertheless, like other missionaries, Williams firmly believed that the hand of God’s providence was superintending the British victory over China in the First Opium War, saying that the war “was the scheme ‘of the God of nations … to open a highway for those who would preach the word. The hand of God is apparent in all that has transpired in a remarkable manner, and we doubt not that He who said He came to bring a sword’ [referring to Jesus’ words in Mattthew 10:34] upon the earth has come here and that for the speedy destruction of His enemies and the establishment of His own kingdom. He will overturn and overturn until He has established the Prince of Peace” (Fairbank 254).

Such misinterpretation of Scripture and misunderstanding of the non-violent way of Christ in advancing his kingdom would return to haunt both missionaries and their Chinese converts in later years, when Christianity was tarred with the brush of Western imperialism. It is true that in 1856 Williams declared that “the English government as such has not the least interest in the progress of China of true religion,” but he went to say that Britain’s assault on China afforded “much to strengthen the hope that God is preparing to work mightily among the Chinese … for further triumphs” of the gospel (Miller, in Fairbank 258).

By 1842, he had completed the Chinese Chrestomathy in the Canton Dialect that Bridgman had begun. In fact, he “furnished about one half of the subject-matter to the volume; in consideration, however, of the just rights of Dr. Bridgman to its inception and plan, he would not allow his name to appear on the title page either as part author or compiler. It was the first practical manual of the Cantonese dialect prepared in China,” and became useful for all students of Cantonese (Williams 105).

In 1842, he was made Corresponding Secretary of the Morrison Education Society.

At the end of 1844, he returned to America by way of Egypt, Palestine, Paris, and London. In Paris, he saw the great collection of Chinese books in their Royal Library and, more importantly, acquired specimens of Manchu type, which he could use in printing Chinese materials. In London, he received a very friendly reception and was able to talk at length with the head of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Here he obtained a full set of Manchu type, which was the main object of his visit.

Back in the United States, he gave more than a hundred long and detailed lectures in churches and other public venues in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, New Jersey, Connecticut, and elsewhere. The enthusiastic response of the audiences convinced him of the value of spreading the knowledge of China – its social life, institutions, history, and spiritual needs, among people at home and laid the groundwork for his later career as a Sinologist among his fellow Americans. He decided to write out his lectures and subsequently published them as The Middle Kingdom, two editions of which came out while he was in America.

His motive for producing this book was “to increase an interest among Christians in the welfare of that people, and show how well worthy they area of all the evangelizing efforts that could be put forth to save them” (155). As one modern scholar writes, “The publication and distribution in early 1848 of the first edition of Williams’s The Middle Kingdom marked a significant event in the history of the Western study of China” (Kaiser 61).

Income from these lectures enabled him to defray the cost of obtaining the font of Chinese movable characters he had found. Indeed, obtaining a full Chinese font, and the funding for it, was the principal aim of his two-year furlough.

Williams not only possessed great knowledge of China, but “was still essentially social in tastes and habits. It was not long before his ready information and his ability as a conversationalist, always a distinguishing trait, became known, and he was on terms of intimacy or of friendship with nearly every person in New York City whose acquaintance offered the slightest prospect of an interest in China or the work of foreign mission… where he showed the art of improving and continuing a friendship once begun without seeming to claim the attention due to long-standing intimacy. This was owing … to the directness and simplicity of his nature… . To him a friendship was a holy as well as a joyous relationship – an impact of heart and mind, the influences of which were for all time” (151).

One such friend was Sarah Walworth of Plattsburg, New York. They formed a mutual attraction while he was delivering a series of lectures, which he followed up with a letter requesting permission to correspond with her further. She must have consented, for they were married in Plattsburg on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1847.

In appreciation of his impressive learning, he was awarded the Doctor of Letters degree by Union College (LL.D.; a degree awarded less often then than later) and inducted into several academic societies, including the American Oriental Society and the American Ethnological Society.

He sailed with his with his bride to Canton in June 1848, after an absence of forty-six months, and landed in September, where he resumed his duties as Superintendent of the Press. His first son, whom they name Walworth, was born in October. As a result of the provisions legalizing Christianity in the Treaty of Nanjing, “for Williams with his new family, all of these changes meant first of all that upon his return to China, he was free to secure housing outside of the factories. This brought him into more normal day-to-day relations with the citizens in and around Canton. He was also able to legally secure a language teacher, as well as to engage in public worship in the Chinese language. Such services had commenced immediately upon the repeal of the ban, and Williams immediately joined in these Sabbath meetings” (Kaiser 63).

He was now able to preach regularly to several congregations, even though he was not ordained.

His son and biographer wrote thusly about the new Mrs. Williams: “It is hard to imagine how out of a world of women he could have chosen one better fitted to round out and complete his nature, or one possessed of a disposition so harmoniously supplementing his own … The rich and tender inspiration of her thoroughly womanly qualities strengthened his moral life, while her strong sense, active head, and determination to surround his home with the external conditions most agreeable and favorable to his tastes, contributed more than any other human cause to the success of his undertakings” (154).

Since the revision of Morrison’s Chinese Bible was underway, Williams also took part in the controversies over the proper translation of the biblical words Elohim and Theos into Chinese. In his article, “Controversy on the Chinese Translation of the Words and God and Spirit,” printed in Bibliotheca Sacra in 1878, expresses his views, which matched those of most American missionaries. He was in favor of using the Chinese term “Shen” because “Shangti will never be understand in any other sense than he now is – the active exhibition of the soul of the universe, which no one but the emperor is permitted to worship” (167).

Bridgman was now able to move to Shanghai, one of the treaty ports. After Bridgman’s departure in 1848, Williams took sole charge of the Chinese Repository. Later, circulation had fallen so much that the decision was made to cease publication of it altogether. Williams cited the greatly reduced interest in things Chinese by foreigners as an indication that the periodical was no longer valued. He did, however, begin to compile and publish an annual “Anglo-Chinese Calendar,” containing much information, plus a brief summary of events in China the previous year and list of foreign residents in the ports in a small book of about 100 pages.

Despite the treaty with China guaranteeing the safety of foreigners, implementation of the treaty provisions was uneven, depending upon local conditions. Even in Macao, the situation was volatile, as local Chinese expressed hatred against foreigners. Living conditions were difficult also, partly because of the oppressive heat. In September 1849, he wrote:

I am getting up and out a Vocabulary, Chinese and English, a Tonic [tonal] dictionary – as Sarah says, to be taken in small doses. I make almanacs … I tend babies at intervals; I preach at Dr. Parker’s hospital every Sunday morning; I am writing the annual mission letter, while others of the mission are declining it; and lastly, I write more letters than I wish to be obliged to on every subject and for every body, settle all the bills of the Fuchau missions, look after all the bundles, letters, boxes, barrels, bales, and business of this and other missions. I tell you I have almost no time to eat, and often get up from my dinner to see if a job is being printed correctly … Yet I am where God has placed me, and where I try and do his work.

It is bad for our missionary operations living as we do in such an unsettled political time, and surrounded by people who rail and sneer at us; our progress is slow, indeed discouraging at times but we feel that this feature is as much a part of the whole face of things as any other, and quite as much under the controlling power of God as the idolatry, the priesthood [of Roman Catholics in Macao] or any other obstacle. Our preaching is listened to by few, laughed at by many, and disregarded by most… . The succession of political troubles, disasters by sea, the news of death and change at home, the experience of troubles here, combine to produce a sense of instability in living in China, which is much like [journeying on a boat]. One gradually acquires a feeling of I can’t tell what unfixedness, the result of abiding in a community so changeable. It should lead us to set all our affections on high, to live loosely to everything but heaven … but I fear for me much it does not have that effect” (172-173).

Clearly, missionaries were human!

He also took very seriously his obligations as the father of a young child: “Nor were the responsibilities of fatherhood taken lightly by Williams, or relegated entirely to his dear Sarah. As he writes upon his son Walworth’s birth, ‘It is a new sensation to hear the wailing of one’s own child and feel that an immortal spirit has been entrusted to our care to bring up in the fear of God and consecrate to his service. I feel as if this dear boy was more in my keeping than all the Chinese, and that his salvation more depended upon me than upon any other person’” (Letter to his brother from Canton on February 24, 1849. Williams 164; Kaiser 65).

At about this time, Chinese began emigrating from southern China to America in great numbers, many to work on the Trans-Continental Railroad. Williams was among the first to see how well the Chinese worked, and how, comparable to other settlers, “what good character they bear in general … being more peaceable, quiet, industrious and manageable than almost any others… . I hope some good to China may result from the thousands now gone and going off to the Universal Yankee Nation” (177).

In 1853, he was appointed interpreter to the American expedition to Japan, leaving from Macao in May. After successfully completing their mission, the party returned to Hong Kong in August. In January 1854, he again accompanied Commodore Perry’s squadron to Japan, where they negotiated an important treaty between America and that nation.

During these two trips, Williams acted as oral interpreter for Perry and oversaw the writing of the English language treaties in Japanese and the translation of the Japanese versions into English – a testimony to his linguistic brilliance. He also demonstrated diplomatic skill as an essential aide to Perry in the complicated negotiations with Japanese officials. His familiarity with the “most favored nation” clause in the Treaty of Whampoa between China and France enabled him to have the same stipulation included in the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa.

Williams hoped that the opening of Japan to commerce, diplomatic relations, and friendly interaction between Japanese and foreigner would also allow access of the gospel, which was, of course, his primary objective in participating in such diplomatic work that took him from his beloved press.

On the way home, he translated the novel Records of the Feudal Kingdoms into English and later published it in 330 pages.

Commodore Perry wrote highly of his performance: “Your services were almost indispensable to me in the wonderful progress of the delicate business which had been entrusted to my charge. With high abilities, untiring industry, and a conciliating disposition, you are the very man to be employed in such business” (230).

He returned to Hong Kong in July 1854.

Commodore Perry reported on Williams’s outstanding part in the negotiations to the Secretary of State and the president, recommending that he be appointed secretary to the American Legation in China. When the request that he enter the diplomatic service came, Williams did not want to accept the honor, for he was afraid that it would interfere with his work as a printer and missionary.

His initially great reluctance to serve with the U.S. Government gradually fell away, however, because his mission made it clear that they wanted to downsize, and even terminate the operation of his press, as they had in other countries. Not only so, but their leader Rufus Anderson now said that not only was the oral preaching of the gospel the primary task of foreign missions, but it was the only proper task of missionaries, or at least of those connected with the American Board. He went so far as to state that Williams had undertaken a “secular job” when he should have restricted himself to explicit gospel work.

Williams defended himself by pointing out that only by printing “secular” materials such as the Chinese Repository and his other writings about China was the press able to sustain itself financially, since the American Board was unable to send them sufficient funds just to live. He insisted, furthermore, that these “secondary” means of disseminating truth were in themselves worthy of missionary labor (Kaiser 71-73).

Anderson may have also been critical of Williams for his strong stand toward China when he was temporarily serving as Secretary of the American Legation.

Then a fire set by Governor Ye in Canton settled the matter by destroying the Canton press entirely. Williams still thought that he should remain in China to “do some good” for the Chinese whom he loved, but he had no way of supporting his family.

Consequently, he was officially appointed Secretary of the American Legation in 1856 and resigned his connection with the Missionary Society the next year.

While Williams and W.A.P. Martin assisted American diplomats in fashioning the Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin) as translators, they strove to win new rights for missionaries in China and to require the Chinese government adopt a policy of religious toleration. More than that, they exercised their influence to have the treaty include the right to teach and preach Christianity not only to missionaries but also to Chinese Christians. In fact, “Williams was responsible for the insertion into the treaty of the ‘religious toleration’ clauses, protecting native converts as well as foreign missionaries and … making the American government in effect a partner in the missionary enterprise” (Arthur Schlesinger, in Fairbank 349).

Nor did they oppose the action of the French missionary who, by a subterfuge, inserted into the Chinese translation of the French version of the treaty the right for missionaries to buy and lease property in the interior of China, outside the five treaty ports stipulated in the treaty provisions.

After Mr. Ward arrived to assume the leadership of the American mission, Williams sailed with him to Shanghai in May 1859, where they engaged in negotiations with the Imperial commissioners. Then they went to Beijing with Ward. The British had been badly repulsed when they tried to force the forts guarding Tianjin, but the Americans were courteously received at the capital. Williams thought that the coming of the British with force threatened the Chinese and made them doubt their peaceful intentions, whereas the unarmed Americans were welcomed. Williams believed that such a friendly approach had worked much better than the aggressive policy of the English, for whom, in general, he lacked much respect in this regard, especially given England’s aggressive promotion of the opium trade.

Nevertheless, the Americans refused to kowtow before the emperor, having been informed that the Chinese considered this a religious observance. The emperor, on his part, would not consent to receive them unless they did obeisance to him. The two sides reached a compromise: the letter from the American president was presented to the emperor by an intermediary and the treaties were ratified by both sides in another location. At no time, Williams notes, were the Americans threatened in any way by their hosts, who escorted them safely back to their ships.

His last act as an officer of the American government was to secure the release of more than three hundred men who had been sold into the coolie trade, which he abhorred.

Williams left China for America in 1860 and stayed until 1861, visiting family and friends, giving lectures on China, resting, and catching up on the situation in America, then embroiled in the Civil War. He hated slavery and welcomed its abolition, by force, if necessary, as now seemed apparent. He would not, however, remain in American to serve, for he knew that his place was in China, serving as a Christian diplomat.

Third term in China

Williams set sail for China in June 1861 with his wife and his youngest daughter. The two older children remained in the United States with his brother Frederick.

Upon their arrival in Hong Kong, they received the tragic news of the illness and death of their oldest son, Walworth. He had placed high hopes upon the boy, and “the disappointment of a thousand cherished dreams for his future made this affliction perhaps the most severe that ever befell him” (330). In the extremity of his sorrow, he wrote, “We know, indeed, who has thus taken away our first-born and transplanted this flower from our garden to His [that is, God’s], but the severance is none the less grievous” (331).

When they reached Shanghai, Williams learned of another loss, almost as terrible: Elijah Bridgman, his close friend and colleague of twenty-eight years had died in the prime of life. His comforting letter to Mrs. Bridgman reflects Williams’ love for her as well as for his friend and his sure hope of reunion with his son and his friend in heaven.

Anson Burlingame, the new American Minister to China, arrived a month after Williams returned to Macao. The British and French had by then captured Beijing, humbling the emperor and forcing upon him and his nation the right of foreign diplomats to reside in Beijing. They had to wait in Shanghai for several months, however. Williams used this time to produce a revised and greatly expanded edition of his Commercial Guide, at 670 pages now containing information on all the ports which had been opened to foreign trade and residence, as well as the texts of all the treaties and regulations governing foreign relations with China. Like previous editions, it became an indispensable guide for merchants, diplomats, and missionaries.

“The Gospel and Civilization – Which is to go first?”

As the nineteenth century progressed, so did notions of cultural progress, by which civilizations can be brought from a “lower” level to a “higher” one, chiefly by education and modernization (as we would now term it). Critics of unwise and hasty evangelistic methods employed by some Protestant missionaries claimed that “civilization” was “a necessary requisite to the introduction of Christianity” (Williams 350). They said that missionaries “ought to teach them the arts of civilized life as a stepping-stone to the truths of revelation.”

Increasingly, missionaries voiced this same opinion, Timothy Richard being perhaps their leading spokesman.[1]

Williams totally rejected this view.

On the contrary, he argued, “the only way to elevate and civilize a pagan people is to preach the Gospel to them in all its fullness of precept and exemplify it by every form of benevolent action.” He continues:

But there is a reason for preaching the Gospel first as a means of introducing civilization, which lies in the nature of the human mind, and to overthrow the argument of such writers… . It is tersely expressed in the words of Christ: ‘And the truth shall make you free.’ The reason why civilization cannot precede in this great work is because it never teaches the truth to the people; it never presents to the mind those sanctions [that is, rewards and penalties] for upholding and reverencing the truth which are alone found in the Word of God. Until the mind of man feels that its inmost sins and thoughts are known to an All-Seeing Eye, there is no restraint upon them: for no god in the pantheon of any heathen people was ever endowed with the attribute of omniscience; it is altogether beyond the ideas, as it is against the wishes, of sinful man.

Until the sanctions of the Bible come to aid the missionary in his teachings, by the Holy Spirit impressing upon the soul its accountability for its violation of God’s law, he knows that his teachings have no power to alter their conduct. But the effects of the truth upon the mass of a people as a means of elevating them in the scale of humanity are seen as soon as individuals begin to live up to the requirements of Christianity, and a small community of Christians, shining forth amid their heathen countrymen, the light that has newly sprung up in their hearts, becomes a centre of improvement.

Even among a people like the Chinese, who are possessed of the conveniences of life and are held together by an organized government founded on the consent of all classes, the want of truth and integrity weakens every part of the social fabric. Moral ethics, enforcing the social relations, the rights and duties of the rulers and the ruled, and the inculcation of the five constant virtues, have been taught in China for twenty-five centuries, and yet have failed to teach the people to be truthful… . The Chinese have, perhaps, risen as high in the two great objects of human government, security of life and property and freedom of action under the individual restraints of law … But until truth becomes even here the basis of society … the Chinese must remain far below any Christian nation. They cannot progress in civilization until they become truthful… .

Truth alone is the proper aliment for the mind; on it alone can all the faculties acquire their full development; and until they receive it, the conscience will feel no sense of weakness or wickedness such as the Bible describes, and no efforts will be made to come to the light and expand under its genial rays. Consequently, there will be no progress in civilization …

Civilization, even as seen in the most civilized countries, is only the exhibition of the principles of Christianity; and how unwise it is to propose to elevate the heathen by introducing among them the results of those principles before giving them the foundation on which they rise!” (Williams 551-353).

Lest we think that Williams considered Western countries fully “civilized,” he goes on to denounce those “emissaries of evil, who having their minds strengthened by the sublime truths of revelation taught in their youth in Christian lands, but their hearts untouched with a sense of sin, come among this people and teach them even a worse style of depravity,” the result of “pseudo-civilization” in the Europe and America.

His words have been quoted at such length because they sum up the fierce debate that eventually engulfed the missionary enterprise, both in China and back home, as the “fundamentalist – modernist” controversy, beginning in the 1860s, when these lines were written, erupted into an all-consuming conflagration in the twentieth century.

Williams also opposed Timothy Richard on the question of ancestral rites. While Richard, W.A.P. Martin, and others argued that these rites were only acts of respect and gratitude toward one’s deceased elders, Williams joined Hudson Taylor and the vast majority of missionaries in showing that the rites also included the offering of incense, prayers, and sacrifice, and thus constituted “worship” rather than merely respect.[2]

The Taiping Rebellion

Unlike some missionaries, Williams “had no faith” in the Taiping movement, “from the first, as likely to promote the truth, for there was no adequate cause for insuring such a result, while the conduct of the rebels during the last five years has shown a ruthlessness and fanaticism enormously greater than when they began their career of slaughter in 1850” (Williams 356).

As with the debate about missionary methods, so with the Taiping insurrection Williams was ahead of many of his contemporaries in seeing the potential dangers long before they fully appeared.

Diplomat in Beijing

He returned in 1862 to the U.S. Legation in Peking, where he remained until 1876, several times acting as head of Legation. During these years, he also wrote his most important language reference work, A Syllabic Dictionary of the Chinese Language (1874).

When peace had been established, Burlingame enunciated, and followed, what came to be known as the “cooperative policy,” which “guaranteed to China her autonomy and treatment on the same terms as any other independent power” (Williams 358-359). Williams heartily endorsed this new approach, which replaced the former pugnacious attitude of foreign merchants and diplomats alike.

After Burlingame returned permanently to the United States, Williams was left in full charge of the American mission in Beijing. One way he expressed his desire to support the Chinese government was to enforce the laws regarding foreigners who committed crimes against it, though without the use of torture routine among the Chinese. He hoped thus to educate them in Western ways of dispensing justice. He felt that in this way God was “employing His agents to make Himself known in one way and another in this land” (Williams 360). In other words, he viewed his service as a diplomat as a natural extensive of his career as a missionary, with the same end: to benefit the Chinese people.

In another attempt to show respect for his Chinese hosts, Williams, at great cost to himself in energy and finances, had a residence for the American Legation built that would be suitable for hosting Chinese officials. “His reward came when Prince Kung, arriving in a sedan [chair] borne by eight men to the inner door of Mr. Burlingame’s house, exclaimed, ‘This is at least decent!’” (Williams 364).

Always a missionary

At the same time, he continued his literary labors, working hard to complete his dictionary of Chinese. Though he considered much Chinese literature as “(to our taste) destitute of imagination, and making a dictionary to elucidate it … a drudgery,” he knew it would help other Westerners to understand the rich legacy of Chinese writings (Williams 360).

With the end of the Taiping rebellion, China lay open to missionaries to settle and work unhindered. Williams constantly advocated for more workers to be sent from the home countries and was frustrated by the slow response. Still, he believed that God had good plans for China’s millions and would accomplish his saving purposes regardless of man’s disobedience. “I begin to think that we shall not have to ourselves the honor of establishing the Gospel in China, but that this in future will be the work of natives more than ever it has been in the past” (Williams 362). How prophetic these words have proved to be!

Always a “scientist”

From his youth, Williams was gripped by a passion to know and understand the world around him, whether it be Chinese civilization or language or the universe of plants and flowers. He possessed an astonishing ability to take note of details and to record them accurately in his notebooks and letters. The same powers of observation and analysis that enabled him to notice and record the flora of his native land and of China equipped him to compile one work of Chinese philology after another.

In 1867, he wrote to his friend Professor Dana:

I am still at work at my dictionary, a plodding and uninteresting, but useful job … There are more than 3,000 characters yet to examine, and six or eight is a good day’s work. None of my previous books on this language are extant, all having been sold or burned up. They did some good, however, in their day, and are still in service to some extent, I hear. This dictionary will be about the last performance I shall undertake, though I have a MS. [manuscript] of a Chronology and Gazetteer so far ready for the press that a few weeks or months would finish them.

I have been busy these last two summers in collecting plants in this vicinity, which I send to Dr. Hance, a German at Whampoa, who has more knowledge of Chinese plants than anyone else… . I collect these plants as well to teach my children how to look at things (Williams 365).

In the same letter, he spoke of his great desire to collect some fossils and insects as well. His biographer adds, “Nor was he unobservant of the simple country people whom he met in the streets or country lanes. He loved to give them kindly salutations, adding at times some questions as to the welfare of whose whom he knew, and a bit of friendly help to those in need. His name and those of his children became in time well known to these poor peasants, and to this day its fragrance lingers in their comfortless homes” (Williams 368).

Williams loved to travel in the countryside around Beijing and to take long trips into the hinterland of China, where foreigners seldom went. He seemed inured to the hardships of the road, while totally engrossed in the great natural beauty of the hills, valley, mountains, and plains of Mongolia and northern China generally. From these remote locations he penned descriptions of people and places that bring the sights vividly before the reader’s eyes. Often invited into farmhouses and Mongol tents, he describes them with such clarity and vividness that you feel as if you are sitting there with him, sipping tea or drinking the milk of a yak or local variation of cattle. It was the same with the colorful dress and ornate hairstyles of the women: nothing escaped his attention, and everything received equally skilled notation.

The next year he was still working on the dictionary, his progress greatly hindered by the need to supervise the construction of suitable premises for the Legation, including a house for the secretary. As he told a relative, he had to oversee every aspect of the work, down to the smallest detail, such buying nails, measuring the door jambs, showing the workmen how to put in bolts, and constantly watching them to make sure they followed his directions and stayed at the job. The marvel is that he knew how to do all these things, as well as his scholarly and diplomatic duties.

What impelled him to such perseverance?

“The Gospel must first be preached to all nations… . preached intelligently and clearly that the race for whom Christ died may know why he died, and this work has not yet been done,” though he was cheered to know that the minute fruits of initial missionary work in China had grown greatly since he first arrived: “So as I look backward I am refreshed for looking forward, and the more willing to bide God’s time in this undertaking which seems immense only to our little selves” (Williams 375).

Years of lonely service

After Burlingame, the successive ministers [ambassadors] from the United States stayed for too short a time to learn enough to be useful. During the interims between appointments, the charge of the Legation fell upon Williams’s shoulders at least eight times. None of America’s diplomatic personnel, save Williams, knew how to speak Chinese, much less to read or write it. Williams was more than once recommended for the position of minister, which he was reluctantly willing to take, but political considerations prevailed in Washington.

His wife returned home in 1869, to care for their children and “see after their education and growth in goodness and manners,” leaving him “to work at [his] post” alone (Williams 381). His son and biographer writes, “He accepted thus, for the second time in his life, the hard necessity of sending away his family, after an inward struggle, the severity of which no one who observed the composures of his parting could have measured or even guessed,” but which shone through his letters home. These described his daily life devoid of those whom he loved best.

Dr. W.A.P. Martin, like him an eminent Sinologist, kept him company in his lonely house in the evenings. During the day, he worked at his desk or went out for rides on one of his two horses, his groom accompanying him on the other. Despite the cost of the extra mount and servant, he explains, “Being a high mandarin, I am, of course, required by propriety to have a retinue” to perform all the ceremonial rites of required of men in such a position (Williams 381).

Though sometimes criticized at home for being too old, he received a medal from the King of Sweden for negotiating a treaty with China in 1869.

Burlingame died suddenly while on a mission to Russia on behalf of China, leaving Williams bereft of one of his oldest and best friends, and depriving China of her staunch ally and advocate in the West. Still, in the midst of his own grief, Williams wrote tenderly to Burlingame’s widow, whom he cherished as “one of our dearest of friends” (Williams 382). Letters like these display his warm heart, full of affection, something not always found in scholars and scientists of his caliber.

In general, Chinese were friendly and receptive to missionaries, but there was always the threat of violence, usually stirred up by the literati, “who are just as inimical to us as the Scribes and Pharisees were against new truths brought in to supplant what their position depended on” (Williams 385). They stoked the fires of anti-foreign sentiment with rumors of missionaries eating the eyes of babies who had been committed to them for care, and whom Roman Catholic nuns took in both out of love and in the belief that if they were baptized they would enter into heaven. The massacre of Roman Catholics in Tianjin greatly disturbed the foreign community for a while, distracting Williams from his literary endeavors.

Though Williams recoiled at such violence, he regularly tried to explain the causes of Chinese rage to foreigners. He wrote home to elucidate the complicated nature of the entire affair and the complex nexus of foreign-Chinese-missionary relations. Likewise, when a riot broke out over the removal of a cemetery to make room for an expansion of foreign settlement in Shanghai, he explained that Chinese would always rise to the defense of the sacred graves of their ancestors.[3]

Behind the Roman Catholics stood the French government, which assumed the status of protectorate of Roman Catholicism in China and generally caused a great deal of trouble to China and to Protestants alike by insisting that Roman Catholic priests and bishops be accorded status and honors equal to those of magistrates and high officials. Williams had nothing but distaste for the interventions of France in Chinese affairs.

His brother Fred died in 1871 and was buried in Syria, where he had served many years as a missionary. “In the death of this brother Mr. Williams sustained a loss more grievous in its way than any he had ever known. It was the sudden removal of an influence which inspired him to nobler efforts, as well as a favorite brother whose heart had been joined to his own by a bond of peculiar sympathy since the day when a devoted mother had given them both to God” (Williams 387).

In the same year he visited Japan for the third time and was greatly encouraged to see how the gospel had made some progress there, the fruit of many prayers and much labor by missionaries and Japanese Christians alike.

On his sixtieth birthday, he wrote to his old friend Professor J.D. Dana from Shanghai, where he was overseeing the printing of his dictionary, “I do know … that we have both of us very much to be devoutly thankful to God for, and the feeling of His loving-kindness and presence grows on me every day” (Williams 393). As with tenderness and affection, his warm-hearted piety and closeness to God were not always found among Sinologist of his stature.[4]

The work of printing of the dictionary was protracted and tedious, but he kept at it “in the hope that it is likely to help in the good work of evangelizing China” (Williams 393). Still, he was beginning to feel his age. The vertigo that had troubled him in his youth and prevented him from joining in vigorous play with his friends was becoming worse, yet he plodded on. Finally, his body could take such unremitting toil no longer. He telegraphed his wife to join him, and “she arrived in time to take him to Peking, just as the body of his dictionary was printed and before the fierce heat of summer commenced. His work had almost cost him his life” (Williams 394). It had been a labor of love for the Chinese to whose welfare he had committed himself for so long.

His health was restored somewhat by a time spent at his favorite temple among the hills, and his daughter came out to help him complete work on an index to the dictionary’s 12,527 characters. For English readers, an index was necessary, because Chinese is not an alphabetical language. Thus, a Romanized index was compiled, listing all the characters by their basic sound. Individual characters were then located by analyzing the root, or radical, of which there are 214, and then going to the page number indicated for that particular character. Williams explained all this and much more in an introduction that ran to seventy pages. The entire project was completed during the next winter and spring in Beijing and then sent to the printer. It had taken eleven years of intermittent toil.

Williams Syllabic Dictionary received an enthusiastic response from students of Chinese and especially those with enough knowledge to appreciate its excellence. They particularly praised the explanations and definitions of the characters. They noted the outstanding conciseness and accuracy of his definitions compared with those of Robert Morrison, the great pioneer lexicographer. Dr. Blodget wrote that “this dictionary, as a whole is a treasury of knowledge in regard to China and Chinse affairs, a treasury accumulated by many years of study both of Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries.” When we recall that Williams compiled this massive work while bearing “the onerous duties of his official position, in which frequently the combined offices of Minister, Secretary, Interpreter, and general business agent” for the American Legation in Beijing, the achievement becomes even more remarkable (Williams 399).

Perhaps only those who have played any role in the production of a dictionary of Chinese and a European language can fully appreciate the magnitude of his accomplishment.

Not wanting the missionaries for whom he chiefly intended this invaluable reference work to be financially burdened by its cost, Williams sold it to them at half price. Then he was especially happy when he received notice of a dividend from a company in which he had invested.

Changes

In November of 1874, Williams had the honor of serving as interpreter for the American minister, Mr. Avery, as he presented his diplomatic credentials from the president to the emperor. In his detailed description, he takes special note of the vast changes that had taken place since his first arrival in China. Now, at last, the envoys of foreign powers received the recognition they deserved as representatives of sovereign states of equal status with the ruler of China.

Seriously broken in health, Williams set out with his family in the spring of 1875 on a six-month-long journey through Austria and Central Europe to England, then home. The change of scene significantly improved his neuralgia, but the strain of long years of hard work robbed him of any ability to enjoy “the intellectual and artistic attractions of the great cities, many of which, indeed, his nearsightedness quite debarred him from enjoying” (Williams 408). He did notice, however, the contrast between Roman Catholic religious images and art and the idols one saw everywhere in China, “where the idolatry is effect, unartistic, ungraceful, [and] feels that it has no power over the soul … But when the associations of a pure faith are combined with statues and paintings of consummate art, spiritual things become to us degraded to the level of worldly things, carnal and sensuous” (Williams 408).

Upon arrival in his hometown of Utica, “nothing in his whole life so pleased him as the spontaneous welcome from his friends, which nerved him to a healthier mood, adding a necessary stimulus to the previous benefits of travel and change” (Williams 409).

After he returned to China, the extreme myopia which been slowly coming upon him prevented his resuming work at the old pace, however, so he resolved to resign from the Legation in China and return to America as soon as possible.

Accordingly, he wrote a letter of resignation to the Secretary of State in June 1876. Secretary Hamilton Fish’s warm reply affirmed his great value to his nation:

Your knowledge of the character and habits of the Chinese and of the wants and necessities of the people and the government, and your familiarity with their language, added to your devotion to the cause of Christianity and the advancement of civilization, have made for you a record of which you have every reason to be proud. Your unrivalled Dictionary of the Chinese Language and various works on China have gained for you a deservedly high position in scientific and literary circles. Above all, the Christian world will not forget that to you more than to any other man is due the insertion in our treaty with China of the liberal provisions for the toleration of the Christian religion (Williams 412).

While awaiting his replacement as secretary, in after hours he compiled an index to the Legation archives, which he considered necessary for the informed continuation of all previous American diplomatic work in China.

His worsening eyesight forced him to rest more and to escape the heat of summer at his favorite temple outside of the capital. In July, he invited his fellow Americans to join him at the new Legation for a celebration of the centennial anniversary of the United States.

Always a friend of China

At about this time, news came of the first legislation passed by Congress to limit immigration by Chinese to America, a move he criticized as stupid and sinful. This disgraceful action further motivated him to sail home, where he saw “a continued usefulness in returning to America and raising his voice on behalf of the maligned Chinese immigrants to this hospitable land” (Williams 415).

He left China; on October 25, 1876, the forty-third anniversary of his first arrival in Guangzhou (Canton), and after seventeen years in Beijing. Both Chinese and foreign friends sent him off with the most affectionate and respectful commendations one could imagine, remarking on his remarkable service to China, the United States, and the growth of Christianity in China. Likewise, in Shanghai all the resident missionaries joined in saying farewell to the one who was by then the longest serving Christian in China.

Last Years in America

In 1877, Williams retired to New Haven, Connecticut, where he had been appointed professor of Chinese language and literature at Yale University, the first such position in the United States. The same convocation that announced his appointment also conferred upon him the honorary degree of Master of Arts. He thoroughly delighted in the quiet life of a college town, with its abundance of intellectual stimulation. The endowment that had been recommended for this professorial chair did not provide any income until a year later, so Williams enjoyed full freedom to read, write, converse with academics, participate in Christian worship and fellowship, and generally follow his interests.

“Though never actually called upon for instruction in his department, he made his influence hardly less felt as a factor in the intellectual life of the university. By means of occasional lectures delivered before a great variety of audiences, by notes and articles in newspapers and magazines, more than all, perhaps, by his genial manner in which he encouraged and received the undergraduates who came to his house, his presence and example, became an incenter to all who were brought within the broad range of his culture” (Williams 426-427).

“While his aptitudes and tastes classed him among fellow professors, his varied life and abundant experience had freed him from the narrowness of vision which too often characterizes clever men of science or letters inadequately disciplined by contact with affairs” (Williams 422). He surprised his peers with his extensive knowledge of many sorts, including recent happenings in politics, science, and society. He found it hard to refuse the constant invitations to give formal lectures or participate in small gatherings about China, or to supply pulpits in churches whose pastors were ill.

First and foremost on his agenda was the notorious treatment of Chinese on the West Coast. Many maligned him for his sharp criticisms of “the injustices of a brutal and unchristian persecution: of the Chinese” (Williams 427), but he persisted. In an influential article entitled “Chinese Immigration,” first delivered as a paper and then published as a pamphlet, he defended the Chinese as an old and highly civilized race from whom Westerners have must to learn. A petition to Congress which he wrote and which was signed by many Yale faculty may have helped persuade President Rutherford Hayes to veto a bill that would have expelled Chinese from the United States. His petition pointed out the obvious fact that Americans in China would likely receive similarly harsh treatment if Hayes signed the bill.

When the terrible famine of 1878 devastated North China, Williams was at the forefront of efforts to enlist the aid of Americans for the sufferers. His relationships with missionaries on the scene helped him to organize effective relief for them to administer.

The Middle Kingdom

With the help of his son, Frederick Wells Williams, he substantially revised The Middle Kingdom (2 vols., 1883). The task consumed his best hours for more than seven years, draining his strength but refreshing his mind and spirit, as he poured all his knowledge and experience into a work that “was long the … standard general book in English on China” (Latourette 265).

Revising twelve hundred pages turned out to take more time than composing the original. He had to contend with his failing eyesight, diminished strength, an injured hand, a tremor that impeded his writing, and the constant interruptions of correspondence, calls from people far and wide, and lectures or talks to present, but he rightly considered this project to be worth his best effort.

In 1879, he learned that thieves had broken into the mission in Beijing and stolen two hundred fifty plates of the dictionary that were stored there. Williams had planned to reprint the work anyway, so he used this loss as a chance to revise the parts that needed new plates, bringing the dictionary up to date according to the comments of critics and the latest information. Still, it took time and energy away from The Middle Kingdom.

Death of his wife

His wife Sarah died on January 26, 1881, after a brief illness. Her impact upon him and the entire family had been great:

Her enthusiasm and cheerfulness, joined to a practical wisdom of daily affairs as great as his own, made her precisely that type of womanly excellence best adapted to supplement and sustain her husband’s nature and position. There was an energy and forethought in her conduct, often called into service during the vicissitudes of their married life, which by its courage seemed to lend strength and heart to his own action; and in the control of the family and household she added to his wise principles and sagacity the tenderness of one who sympathized as well as controlled… .

[After her death] his intellectual efficiency and vital energy were alike profoundly affected; his hold on life visibly weakened from the moment her sustaining companionship was removed (Williams 442).

Towards the end of Sarah’s days, he comforted her by reading from the Bible, and after her death these same words promising eternal life strengthened him during the dark says that followed.

Other honors and blessings of growing older

The American Bible Society elected him president in March of 1879. It was intended to honor the whole missionary enterprise, which he was held to represent, as being among the most learned as well as the longest serving missionary from America in China.

A second honor came with his election as president of the American Oriental Society, of which he had been a member since 1846.

With his wife gone, Williams had no one to talk to, so he occupied his mind by contemplating the wonders of creation, the beauty of God, and the riches of scriptural revelation in the Bible.

The older he got, the more he valued such religious customs as prayer meetings. “A prayer meeting is in itself the most honorable meeting it is possible to think of or attend, if it is rightly considered. For a company of human beings to draw near to God, and make known their requests, offer their praises, and unite their confessions and homage, is either a most awful impudence or a most responsible worship” (Williams 447-448).

The increasing weariness of both body and mind, nevertheless, forced him to give over the last part of The Middle Kingdom to his son to revise. At this point, his remarkable humility showed itself in his readiness to accept criticisms and suggestions for improvement in the style or content of the book.

The revised and expanded edition of The Middle Kingdom, in two volumes of about 600 pages each, was completed by his son Frederick in 1883, just before Williams died. This revision substantially modified many disparaging judgments of his early missionary days (Bays 737). His last words about it deserve quotation:

I have endeavored to show the better traits of their national character, and that they have had up to this time no opportunity of learning many things with which they are now rapidly becoming acquainted… . The stimulus which in this labor of my earlier and later years has been ever present to my mind is the hope that the cause of missions may be promoted. In the success of this cause lies the salvation of the Chinese as a people, both in its moral and political aspects (Williams 458).

One historian described this work as “by far the most delightful of all the early attempts to explain China to the West” (Barr 16). For this culminating work and for all his previous studies in Sinology, Williams was widely regarded as “one of the great scholars of the missionary body” (Latourette 218).

Even a brief glance at the contents will suffice to display the riches of Williams’s knowledge of nineteenth-century China. Relying on extensive personal observation, Chinese sources, and the writings of knowledgeable foreigners, he covers, in detail, the Chinese empire’s physical geography, political divisions, government, history, customs, dress, religions, architecture, languages, education, industries, agriculture, literature, commerce, relations with foreign governments, Christian missions, and much else.

As he had hoped, The Middle Kingdom became the standard introduction to China for several generations of merchants, diplomats, and missionaries, including Hudson Taylor, who read the 1848 edition before leaving England the first time. “The Middle Kingdom, at this opportune moment, made the American voice heard in Chinese studies and rid the dependence on Europe for understanding China. Overall, this book provides an accurate and brilliant insight into China and the Chinese” (Guan 115).

Reviews of The Middle Kingdom were almost universally positive, except for several English critics who condemned his “settled conviction that England, by reason of her opium policy, was at the bottom of much of the present misery of China” (Williams 460).

By 1890, his Syllabic Dictionary of the Chinese Language was still selling well enough to help finance the college founded by Devello Sheffield in Tongchow.

Samuel Wells Williams died on February 16, 1884.

Legacy: Scholarship, diplomacy, character

Williams lay the foundation for all subsequent works of Sinology and was the standard for all succeeding American students of China. “Undoubtedly, Williams’ passion for Chinese language and knowledge was largely driven by his original motive to advance Christianity in China” (Guan 114).

“Rather than counting conversion notches on his belt, Williams invested himself in arduous studies to develop and pass on to those who came after him his knowledge and understanding of China, her people, and their language” (Kaiser 24).

Though later events showed that Williams’ early assessment of the obdurate character of Chinese government and the hard reality that only superior force would make them observe treaty obligations – an opinion shared by most missionaries – was correct, the belief that violent measures would advance the cause of the gospel has just as clearly been proven to be completely wrong. Williams and other missionaries obviously forgot the lesson that Jesus had to teach Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane (Matthew 26:51-56). Both Chinese Christians and the legacy of foreign missionaries have labored under the burden of this tragic mistake ever since then.

We must also observe that his inclusion of legal rights for Chinese Christians and missionaries in the treaty negotiations in 1858, and his silence about the unscrupulous action of the French missionary at the same time implicate Williams (AND W.A.P. Martin) in making the U.S. Government a party to the missionary enterprise and in deception. These well-intentioned actions turned out to be disastrous for the future of Chinese Christianity and for the reputation of missionaries among Chinese.

The letter that fellow missionaries wrote to him when he left Shanghai probably expresses his legacy best:

Your kindly cheerfulness and patient industry and Christian consistency have won our hearts, commanded our admiration and given us an example full of instruction and encouragement.

Your labors as editor, author, and lexicographer have laid us all and all students of Chinese history and the Chinese language under great and lasting obligations to your extensive and accurate knowledge and to your painstaking and generous efforts in giving it to others.

The high official position which you have so long occupied as United States Secretary of the Legation and Interpreter, and nine several times as United States Charge d’Affaires, has given you many and important opportunities for turning your knowledge and experience to valuable account for the benefit of the Chinese, the good of your own country, and, above all, for the advancement of the cause of Christianity in China. And we would express our grateful sense of the conscientious faithfulness with which you have discharged the duties of this responsible post.

But especially shall we delight to remember that in all your relations, literary, diplomatic, and social, towards natives and foreigners in China, for the unprecedented term of forty-three years, you have faithfully and consistently stood by your colors as a Christian man and missionary (Williams 420).

In other words, his fellow missionaries recognized that Williams did not stop being a missionary when he needed to be able to support himself and his family in China in other ways after his own mission could no longer do so. To the end, he put his service to God above his service to his country, and he sought the welfare of the Chinese as diligently as the interests of his own nation.

As for his character, letters of tribute that poured in after his death spoke of the “union of reverence and reality”; his willingness to apologize, even to servants and children; a “sweetness and good sense which were the result of his long practice of stern self-control”; his “high and constant sense of duty” (Williams 464-467).

He loved children and they reciprocated his affection. At the same time, wrote his son Frederick, he required his own children to “commit to memory quantities of Bible verses, a certain number each morning before breakfast, without which neither he nor we could have our breakfasts” (Williams 468).

Though a very hard worker, “he never forced himself in any way by excessive hours or night work to do more than his strength allowed” (Williams 468).

Others spoke of his amazingly retentive memory and his knowledge of the Bible which was “quite as astonishing” (Williams 470).

He led a methodical life, but it was “the beauty of his thoroughly Christian character … perfect consistency” of conduct and of “how entirely in thought, word and deed the word of God was the rule of his life” (Williams 471). At the same time, he was very lenient in judging the conduct of others.

A very close and lifelong friend wrote that Williams was “full of good cheer and kindliness, quick-witted, intellectual, and zealously devoted … to the interests of missionary work… . He through life walked with a childlike faith the truths taught him in his early years” (Williams 474). That faith, by the way, was of the Reformed, or Calvinistic type. “He lived and died in the serene and blessed hope of a future happiness which he should enjoy” after death (Williams 475). As a result, he possessed a remarkable peace of mind and repose.

G. Wright Doyle

[1] See especially Eunice V. Johnson, Timothy Richard’s Vision: Education and Reform in China, 1880-1910, in G. Wright Doyle and Carl Lee Hamrin, eds, Studies in Chinese Christianity. Eugene, OR, Pickwick Publications, 2014.

[2] Broomhall, Assault on the Nine, 287.

[3] Broomhall, A.J., Survivor’s Pact, 398.

[4] The autobiography of Timothy Richard, for example, contains no such sentiment, though perhaps his letters do.

資料來源

Publications of Samuel Wells Williams

English